So, you’d like to stack rank your developers?

Sometimes people approach using software engineering intelligence tools with the mindset of “just tell me who’s my worst developer.”

If it was that simple, I’m sure there would be money to be made in solving that problem.

We’ve been in this space for six years. We wrote the top book on running effective engineering organizations. We built a SaaS product with some of the best software companies out there. And we haven’t seen anyone come up with a simple solution that actually works.

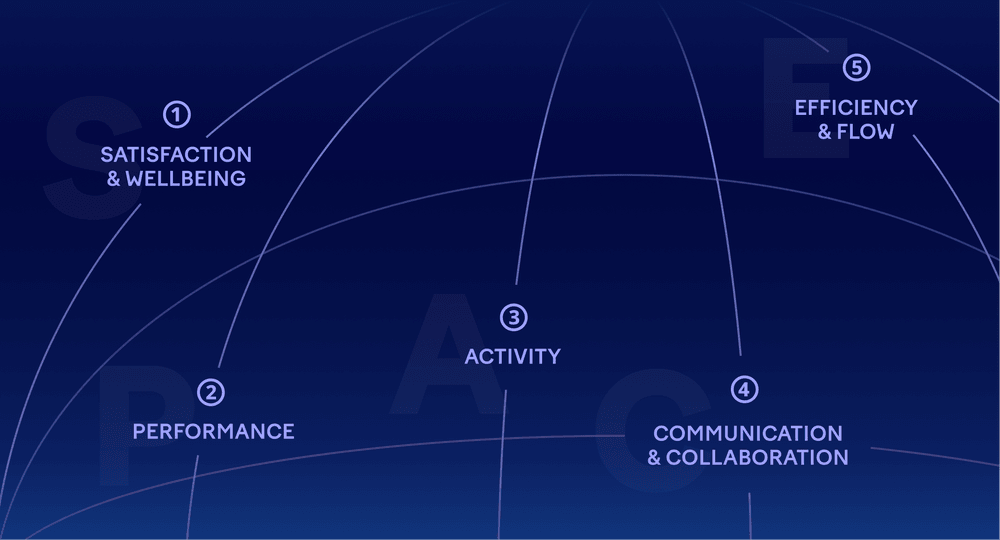

Our observations are aligned with the latest research, including the SPACE framework: there is no single metric, and there is no simple solution.

The allure of simple answers in hard times

In the current economic climate, engineering leaders are again under a whole lot of pressure to “do more with less.”

Boards want to know they’re getting value from their engineering investment, and the rise of AI coding tools has leadership asking whether a traditional engineering function with developers of all levels is truly necessary.

The appeal of stack ranking is understandable. When you need to make hard decisions about headcount, having a ranked list seems simple and logical. When the CEO or the board ask why engineering is so expensive, pointing to productivity metrics feels safer than explaining the complexity of software development.

But stack ranking doesn’t deliver what it promises. Instead of objectivity, you get gaming. Instead of performance improvement, you get knowledge hoarding. And instead of keeping your best developers, you watch them leave for companies that treat them better.

All hope is not lost, though. You can certainly use data to support a more objective performance management process.

But let me first explain why stack ranking individuals never works — no matter how hard you try.

Here’s why it doesn’t work

No matter which metrics you choose or how sophisticated your formula, the same problems are going to pop up.

Aggregate numbers lie

How many commits or pull requests did a developer complete?

Looking at outputs is not completely useless, and there are cases where a developer is not really able to focus on writing code, or doesn’t have the skills to do the job in your environment.

But if you do start looking at this data, you have to take into account the factors causing errors:

- Did they take some time off during the measurement period?

- Are they the person reviewing most of other people’s code in their team?

- Are they working on non-development responsibilities, like scoping product features or interviewing candidates?

There is no standardized measure for output

If two people build the exact same feature from the same specifications, their output will still look different.

We all have personal preferences in how we split code to commits, and how we group those commits to pull requests.

For a more complex feature, you can have different strategies for approaching the implementation:

- Some people will choose a more incremental approach with a quick end-to-end solution and more refactoring.

- Someone will try to aim more directly to the goal, but takes a bit more risk in putting it all together.

- Someone else can do one commit in one pull request, doing the exact same thing someone did over 50 commits and three pull requests.

But the differences are more complex than just style. They might also write different code entirely. You might measure lines of code, but sometimes more code results in more complexity and technical debt. The developer who writes 100 lines of elegant, maintainable code creates more value than the one who writes 500 lines that will need to be refactored within a few months.

A concise solution that’s easy to understand and modify is worth more than a verbose one that technically works but nobody wants to touch. Yet most stack-ranking metrics would rank the second developer as more “productive.”

Some productivity metrics are not applicable for individual developers

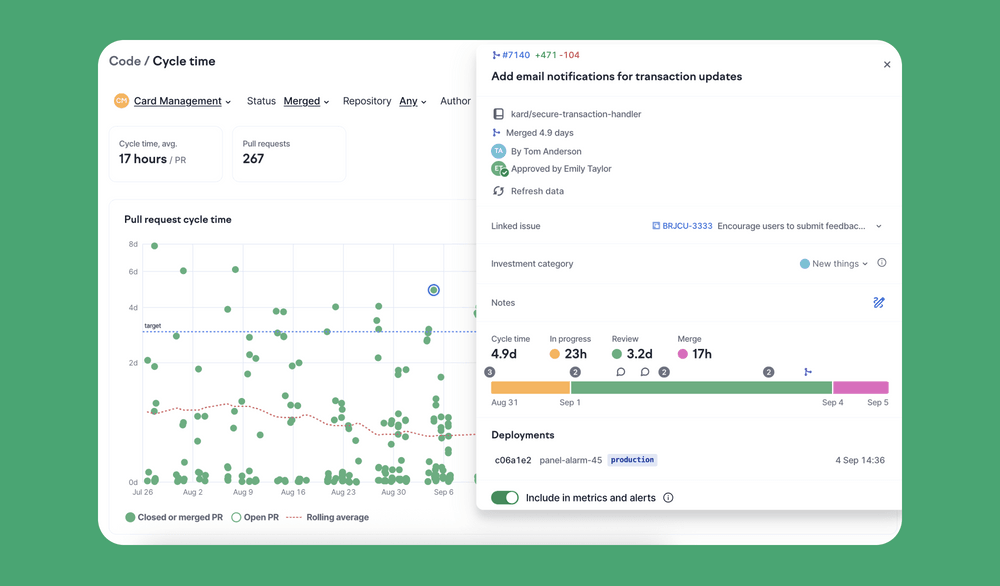

Let’s take cycle time as an example.

Cycle time — the time from first commit to production — is crucial for understanding your development process. But it’s useless for evaluating individuals.

Cycle time is mostly about waiting: waiting for reviews, waiting for CI, waiting for deployment windows. A developer with a 5-day cycle time isn’t slower at programming than one with a 2-day cycle time. They’re probably just working on different types of problems.

There’s also massive selection bias. Senior developers often have longer cycle times because they’re tackling the complex architectural changes. The junior developer shipping UI updates daily is not more productive than the senior engineer spending two weeks on database migration. Both types of work are important, but they’re different types of work.

You need to be close enough to a developer to understand their work

If you’re looking at productivity data across a bunch of teams (who are a few levels below you in the organizational hierarchy), you are likely not familiar with the challenges of that team.

To truly coach someone to do better, you will have to talk about the work — not the numbers.

What’s the feature we were trying to build? What turned out to be difficult about it? Did we foresee all the issues, and was it a team-level gap (as in: no one knew the area), or something that the individual wasn’t familiar with? Were they supposed to be familiar with it? How did we plan the feature, and how did the rest of the team contribute?

None of these things can be deduced from a number.

What actually happens when you stack rank developers

We should all know this by now, but in case we don’t: some rather predictable things happen when you pit people against each other.

- Knowledge becomes currency. Developers stop documenting their work, and they avoid doing things like pair programming. Why help someone else improve their ranking at the expense of your own?

- Collaboration dies down when code reviews become adversarial and nobody really wants to work on shared components. Teams fracture into individuals competing rather than collaborating.

- Gaming the metrics is unavoidable. Even if your developers are not intentionally splitting PRs unnecessarily to boost counts, they might end up picking tasks that are more likely to look good when measured.

- The developers you most want to keep (the ones who mentor others, tackle hard problems, and think about the big picture) are the first to leave. They can easily find companies that value collaboration over competition.

A better approach to performance management for software engineers

Instead of trying to rank developers against each other, focus on helping each person grow. Here’s what we’ve learned about how to build a performance management process that actually works.

Team leads, engineering managers and their managers are in key positions

These are the folks who have all the context about their team’s day-to-day.

Managing performance-related discussions is one of the most difficult things every new manager has to learn, so you can’t just expect them to be perfect. This is why the team’s performance needs to be a regular topic between them and their managers, so they can ideate the best strategies.

You should write down how you expect these discussions to be had.

Have a feedback loop about your engineering managers

Unfortunately, sometimes the manager is the one causing the performance problem.

Maybe they are not deep in their team’s work, and can’t properly evaluate it. Maybe their technical skills are lacking. Maybe the personality clashes with the team. Or they micromanage. Maybe they avoid the hard conversations, and their indecision is the issue.

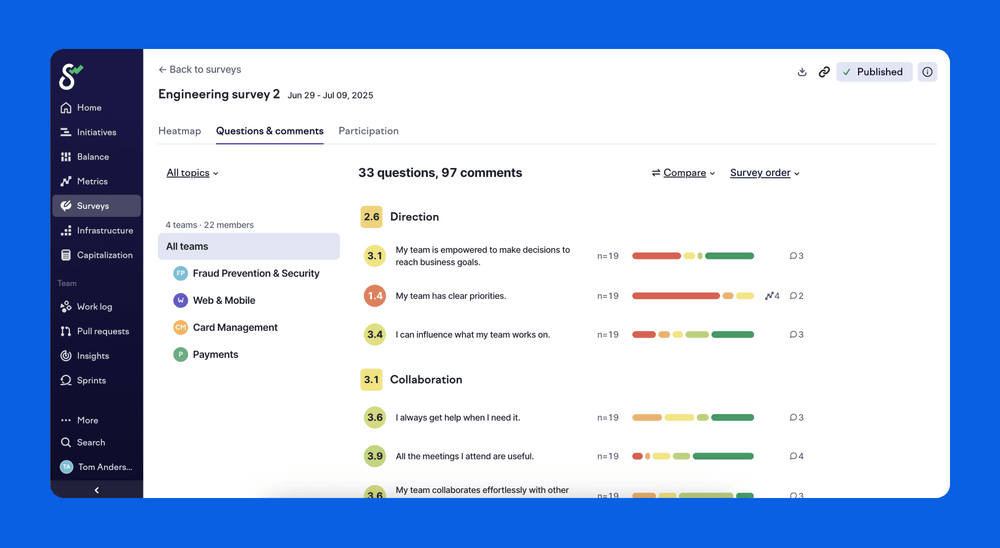

The most common feedback channels are developer experience surveys with your teams, and skip-level 1-1s.

Try to agree on the truths

Before saying how good of a job someone is doing, it’s good to establish the truths we both agree with.

You worked on this feature together with A and B. It was a team effort, and you implemented practically all the backend. It seems to be well-tested, and we got the feature out to first alpha customers three weeks after starting the implementation. Our roll-out strategy could have been better, as we didn’t identify some issues early.

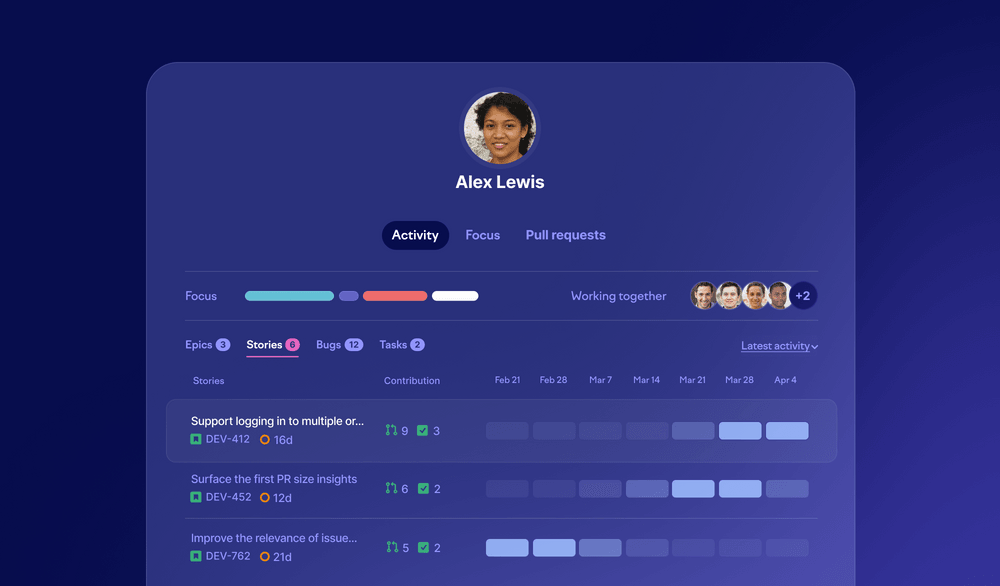

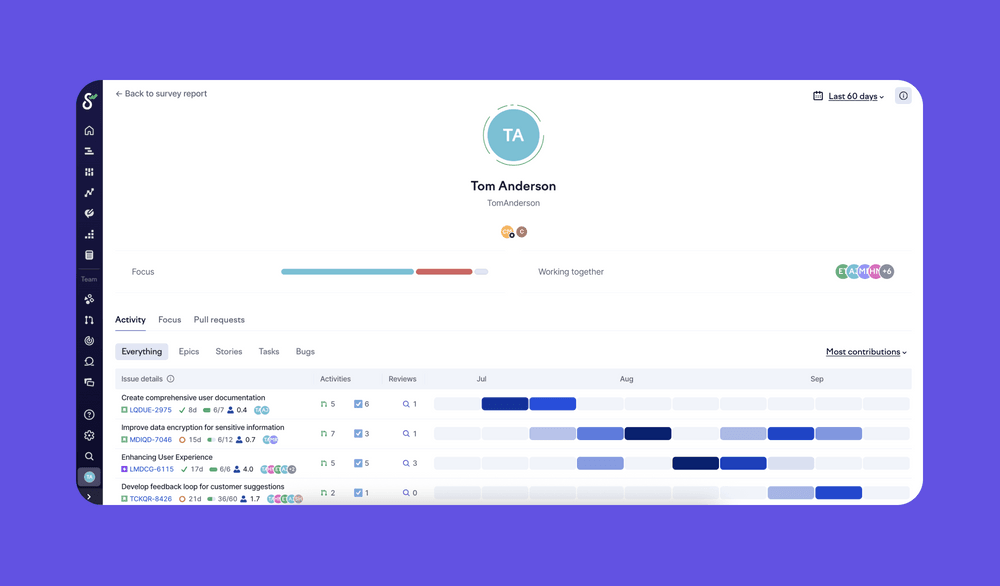

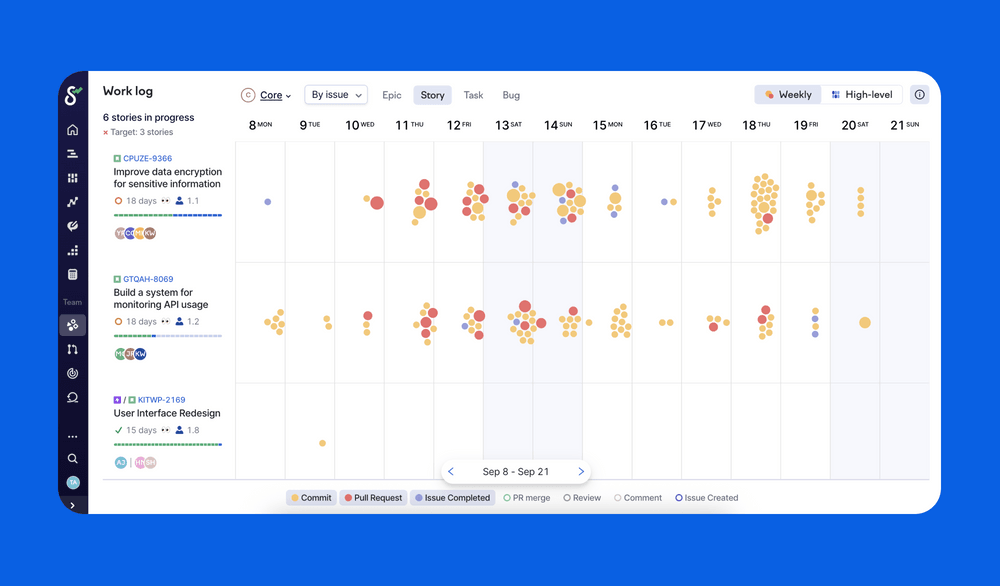

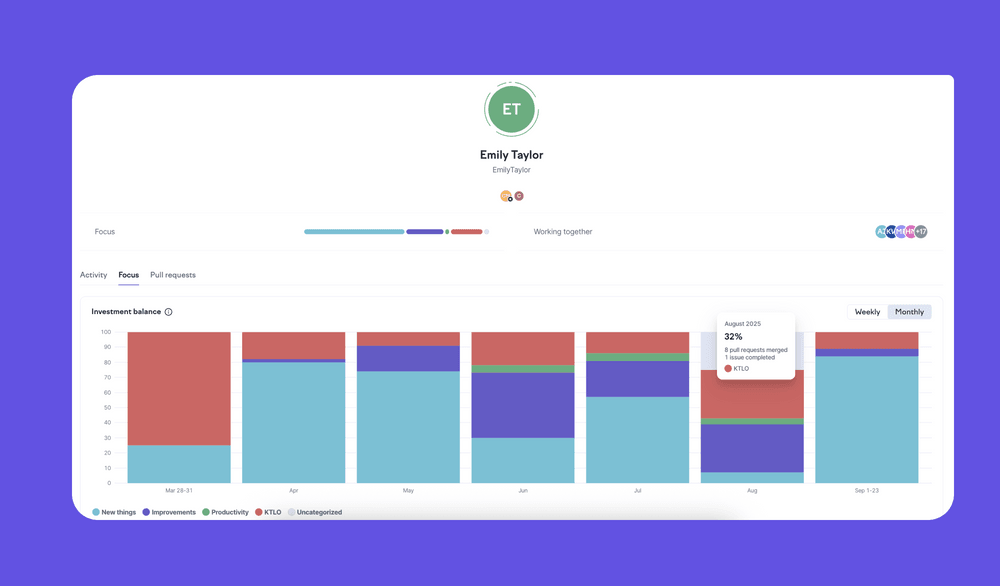

The timelines and outputs are easy to check from your software engineering intelligence tool. A developer-friendly tool doesn’t make judgment calls, but gives you context.

Gather input from other developers

If the engineering manager is not as hands-on (and even if they are), sometimes it makes sense to ask for more input from other developers.

We do this for all new hires, and then less frequently after the first 6 months.

The people who actually review the code are the ones who have an idea about the quality. Sometimes they might have accepted some pull requests reluctantly, or had to rework all of the code as part of the review cycle.

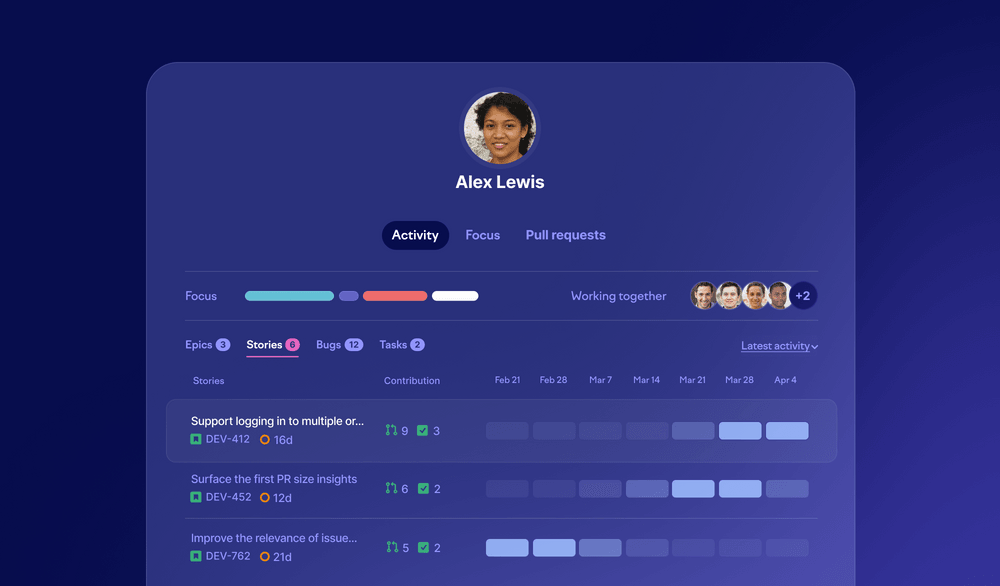

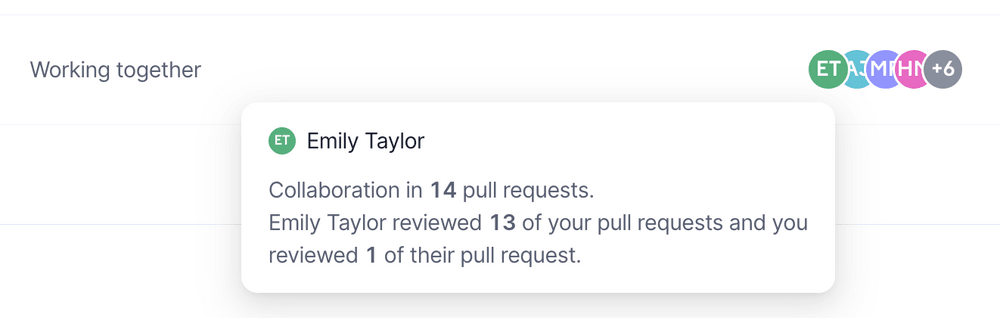

In Swarmia's developer overview, you can see a breakdown of a person’s biggest collaborators.

Talk more about the work, less about the metrics

Metrics are the lagging indicator, and they can’t always explain what’s going on. They are great discussion-starters, and bad conclusions.

Look at the team patterns

A big part of individual performance will be explained by team and systemic factors.

Think of your team as a puzzle — each person is a piece with unique edges and patterns. Some pieces naturally fit together, others need more work to connect.

You can’t evaluate a single puzzle piece in isolation; its value comes from how it connects with others to create the complete picture.

This is why it’s important to be able to see how work flows through the team. Who’s collaborating with whom, where the dependencies are, and how much time is spent on reactive work versus planned features.

If the team has to do some regular firefighting, of course it’s affecting the team’s ability to ship features.

The grunt work is not always distributed evenly in the team. Sometimes a developer will take a big share of the bug fixes and production incidents just from the sense of responsibility.

Build growth frameworks, not ranking systems

Competency frameworks are much healthier than rankings. They give developers clear paths for growth without turning your team into a competition. Focus on what actually matters for each role:

- Technical skills relevant to their role

- Collaboration and mentoring

- Business impact and decision-making

- Leadership and initiative

When you evaluate developers against these competencies instead of against each other, they focus on getting better at their job rather than looking better than their colleagues.

What boards actually care about

When your board asks for engineering productivity metrics, they’re not really asking for a ranked list of developers. They want to know if engineering can deliver predictably, if you’re building the right things, and if you’ll hit your milestones. Team-level metrics and delivery trends answer these questions — stack ranking doesn’t.

Some vendors in this space will still try to sell you a single number or normalized ‘productivity score’ — which is often just lines of code with a few extra steps, dressed up in a bow tie. While it’s tempting to take that single number, I promise you, doing things the right way is a good idea for everyone involved.

It is a lot, but it should be

This solution might be more work than you’d like, but that’s the reality of managing an organization. It’s a real job, where managers need to be interested in seeking the objective truth and understanding the nuance.

Tools can help you facilitate this process, but they will not run your team for you.

As a leader, it’s important we educate everyone about the complexity of this job. In the age of over-simplified social media takes, it’s always attractive to try to find that one number that tries to solve your organizational issues. But it does not exist, no matter what the viral LinkedIn posts say.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest product updates and #goodreads delivered to your inbox once a month.

More content from Swarmia