Small teams, big bets: Lessons from three Nordic AI startups

Just three years into building Inven, Ekku Jokinen’s team secured €11.2 million to scale their AI-powered deal sourcing platform. With data on 21 million companies and 670% year-over-year growth, his engineering team would fit comfortably in one meeting room — while competitors still employ hundreds of analysts to add labels to data.

I sat down with Jokinen and two other CTOs from AI-native startups — Juho Eräste from Taito.ai and Johan Jern from Realm — to understand how they’re building the new wave of engineering organizations.

All three are based in Helsinki, part of a $552 billion Nordic startup ecosystem that’s producing unicorn after unicorn with remarkably lean teams.

Five engineers doing the work of ten

Juho Eräste remembers watching Smartly’s headcount explode from 10 to 1,000 employees, in what he now calls the “pure mayhem” of traditional scaling. In 2024, Juho started Taito.ai, an HR tech platform that uses AI to improve performance management processes and help people grow as employees. And he chose to scale differently: to grow revenue, not headcount.

“Five years ago, five engineers meant you're barely functional,” Eräste tells me. “Today we’re shipping features that would have taken a team of ten.” His estimate of 2x productivity gain sits between industry hype and reality.

We might be 2x more effective than without these tools, but when you move towards bigger and bigger teams, the bottleneck is most likely not the speed at which people can type; it's something else entirely.

Taito.ai

Johan Jern at Realm, which turns company knowledge into AI agents for revenue teams, takes a similar approach. Since founding the company in 2023 with fellow former Slush leaders, backed by Lifeline Ventures and founders from Zalando, Wolt, and Supercell, he’s maintained focus on keeping his engineering team small.

“You need to prioritize because there’s more stuff to do than you have time for,” Jern explains. The alternative creates teams that lose momentum chasing unclear objectives. It takes discipline to resist solving every problem by adding headcount.

But keeping teams this small means both laser focus and outsourcing menial and tedious tasks to AI. Documentation, test writing, boilerplate code — the mechanical work that used to eat up hours. One thing that does remain stubbornly human, however, is code review. While AI assists with the process, each of the three companies ensures a human is always part of code review.

“In a very small team, everybody kind of knows everything. And that’s super useful,” Jokinen explains. This shared context becomes its own competitive advantage. There are no knowledge silos, no communication overhead, and no waiting for the one person who understands that particular system.

When you have 100 engineers, the relative output of an individual engineer is not huge. But when you have like 5 or 15? Every individual matters a whole lot.

Inven

Velocity is the competitive advantage

Speed shapes every decision at these companies. At Inven, developers choose their own tools: Copilot one week, Cursor the next, Claude Code when someone's curious. At Realm, adoption happens organically when someone tries a new tool, shares it with the team, and others give it a shot too.

This level of informality wouldn’t fly at most enterprise IT departments, but flexibility and experimentation matter more than standardization when the capabilities of these tools evolve weekly. And for what it’s worth: nobody is signing up for multi-year contracts with any AI coding tools yet.

Jokinen’s team prioritizes rapid iteration over comprehensive planning. “Speed of execution wins right now,” he explains. For Inven, this means that formal processes and comprehensive testing can wait until the model is proven.

AI tools reduce the friction of writing code, which fundamentally changes how teams validate ideas. When implementation is faster and cheaper, engineers can test an approach, discover it's flawed, and pivot to something better — all in the time it would have previously taken to build the first version. For companies still searching for product-market fit, this compression of the learning cycle matters more than raw output.

The work that can't be accelerated (deciding what to build, understanding customer needs, architecting systems that scale) now takes up a larger share of engineering time. The craftsmanship that matters happens at the product and system design level. Code implementation, while still requiring skill and oversight, has become less of a constraint.

Size provides natural safeguards for this level of velocity. “You feel it” Eräste says simply about knowing when something’s wrong with just five engineers. At fifteen developers, Jokinen maintains visibility through regular 1-1s with his team. But what happens at fifty? At a hundred? Nobody knows yet.

Productivity gains come with caveats

The productivity gains these CTOs report aren’t quite as simple as they seem. Yes, they’re shipping faster with smaller teams. But the picture is more complicated than the 2x claims suggest.

“For most experienced engineers, it’s been more about removing annoyances, rather than massive productivity improvements,” Jokinen admits.

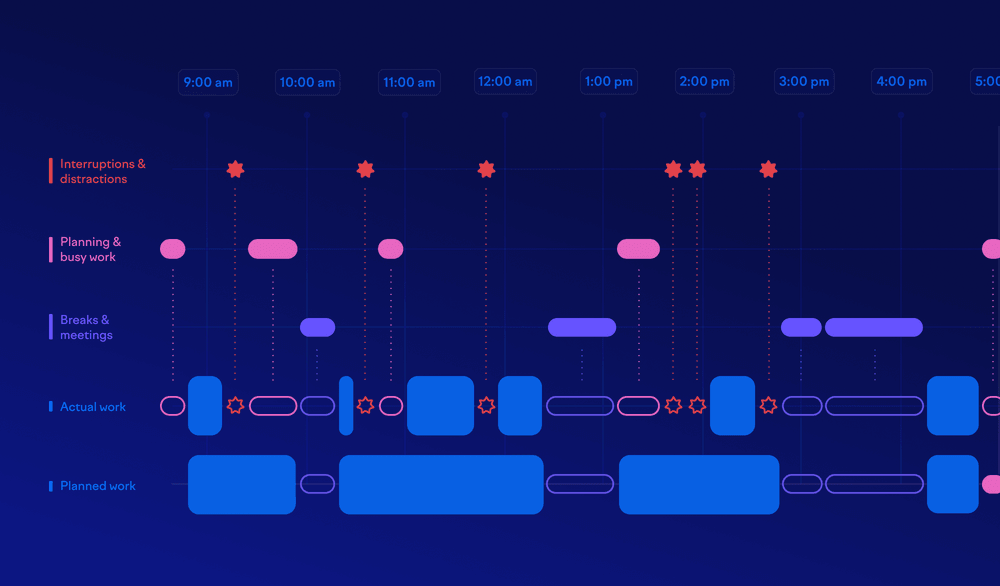

This tracks with broader patterns in the industry:

- A Refactoring survey of 435 engineers found that 77% use AI daily and 54% save five or more hours per week — but mostly on simple, repetitive tasks. The engineers happiest with AI aren’t using it for high-value work, but for documentation and boilerplate.

- A LeadDev study of over 600 engineering leaders found that 60% report no meaningful productivity improvements from AI tools. Code quality emerged as a top concern, with 51% of leaders believing AI will have negative long-term impacts on the industry.

Yet speed and quality both miss the bigger question that AI doesn’t answer: are you building the right thing?

As a startup founder, your biggest risk is building something nobody wants. And AI doesn’t help you with that.

Realm

Looking for cracked, not just competent

Despite literally building AI products, walk into technical interviews at any of these companies and AI proficiency barely comes up. “We typically ask your take on AI,” Jokinen says,“but it doesn’t really affect the hiring decision.”

So what are they really after?

Engineers who can structure problems clearly enough to guide AI effectively.

Jern calls it the “hacker mentality”: the developers who were already jumping between problems, fixing things quickly, maintaining quality despite constraints. The kind of engineer some might these days call cracked. Relentlessly capable, weirdly productive, thriving in chaos.

“I look for strong generalists with expertise in one area,” Jern explains. These engineers treat AI tools like any technology in their stack, understanding both the power and the sometimes painfully obvious limitations. Often, they’re the ones who would thrive with or without AI assistance, which often makes them best positioned to leverage it.

The ideal profile hasn’t shifted much since pre-AI days. What has changed is who gets filtered out: engineers who would “drown if all these AI tools went offline,” as Eräste puts it, don’t make the cut. The same goes for engineers refusing to adapt to AI at all.

Interestingly, all three companies are building their teams in person in Helsinki. When you’re running this lean and iterating this fast, being in the same room does matter — because of the quick whiteboard session, the overheard conversation, and the ability to immediately hash out why the robot just generated something weird.

What about junior developers?

At Inven, Jokinen’s team values hunger and drive over years of experience. “We look for the drive that typically comes with people earlier in their careers,” he explains. “But we have been able to find a few super senior people that still have that hunger for growth.”

Realm takes a similar approach, with about a third of its team being junior developers. To them, when you combine AI tools with the right mentorship, skilled and driven juniors can punch well above their weight, performing at levels typically expected from more senior engineers.

Taito.ai, on the other hand, hasn’t hired any junior developers yet. “But I would hope to, because if we stop hiring juniors, fast forward 20 years, there’s not going to be any seniors out there.” Eräste acknowledges. He also sees opportunity:

If I were a junior, it would be kind of scary because companies are hiring fewer juniors. But the juniors who are hungry to learn will have AI as the best teacher they could have.

Taito.ai

The question is whether juniors can learn as effectively when AI handles much of the mechanical work. “Maybe the raw mechanical repetitions of writing code — that's harder to get good at when there's a shortcut," Jern reflects. “But the broader knowledge part is easier because you can ask and see what AI does, and think about why.”

Hiring juniors requires something some lean teams lack: senior engineers with bandwidth for mentorship. When you’re deliberately minimizing headcount, developing talent requires intentional investment that some teams can’t prioritize.

As one industry observer argues, AI won’t kill junior developers, but companies’ refusal to hire and train them might. The threat is the short-term thinking that sees juniors as expendable when AI can handle what used to be seen as ‘junior tasks’.

The high-stakes bet on lean teams

What’s happening in these Nordic experiments goes beyond building good products. These companies are redefining how software teams work when implementation becomes cheap and judgment stays expensive.

While traditional engineering organizations carry decades of accumulated processes and dependencies, these startups are designing organizations assuming AI exists, rather than retrofitting AI into organizations built assuming it doesn’t.

It’s a high-stakes bet. Will this approach deliver lasting business value when the AI hype settles? For startups betting everything on this model, there is no plan B.

But then again, for companies competing against incumbents with 100x their resources, there never was.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest product updates and #goodreads delivered to your inbox once a month.

More content from Swarmia