Is your software engineering intelligence platform really developer-friendly?

Many software engineering intelligence tools market themselves as “developer-friendly.” It makes sense, because developers are rightfully suspicious about the category. They’ve seen these tools used to stack-rank them, reduce their work to meaningless numbers, and create surveillance cultures that destroy psychological safety.

When the market was hot and engineering talent was scarce, being “developer-friendly” was good for business. Companies had to keep their developers happy. Once interest rates increased and the job market shifted, many of these tools quickly forgot about this messaging. But their products never really reflected it anyways.

Depending on your organizational culture, developer-friendliness might either be table stakes or something that would be nice to have — after you’ve satisfied the board and shareholders, of course.

In reality, developer-friendliness is not just about developers. Software engineering intelligence tools exist to help you make better decisions and to improve business outcomes. If your developers are not involved, you will just get an illusion of control, and you are unlikely to drive any improvements.

What makes a product non-friendly for developers

There’s a pattern to how these tools fail developers. Once you know what to look for, you’ll spot the problems immediately.

Limited transparency and asymmetric information

Imagine this: your manager just bought a new tool to decide who gets a promotion and a raise, but the employees don’t have access to this information.

Later you find out that the data in the tool was incorrect, because your team uses Jira in a different way, which meant people who deserved recognition didn’t get it.

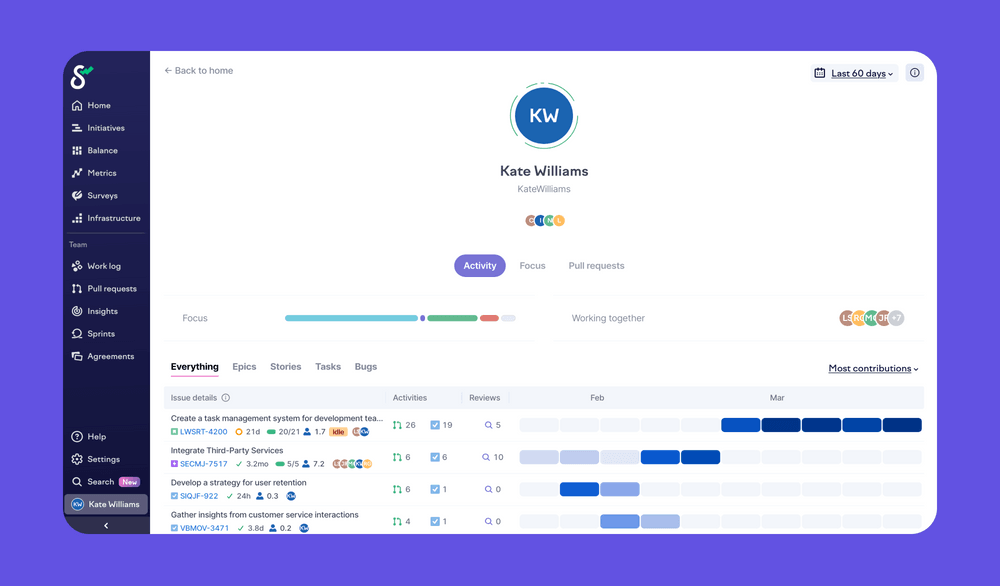

The data in any tool is most valuable when people can look at the same “truth” and reason about it, together. Observing things from the outside is not the way to go.

When developers are measured by metrics they can’t see or influence, it creates an adversarial relationship. Time gets wasted gaming metrics, documenting why metrics are wrong, or working around the surveillance rather than building software.

The psychological safety required for continuous improvement evaporates. Instead of collaborating to get better, developers spend their energy defending themselves.

Treating metrics as a conclusion instead of a discussion-starter

Software engineering is a complex job. We design features, run product discovery with the product managers, scope down features, unblock dependencies, follow adoption metrics, review code, coach our colleagues, and provide support to other departments — on top of doing the actual programming work.

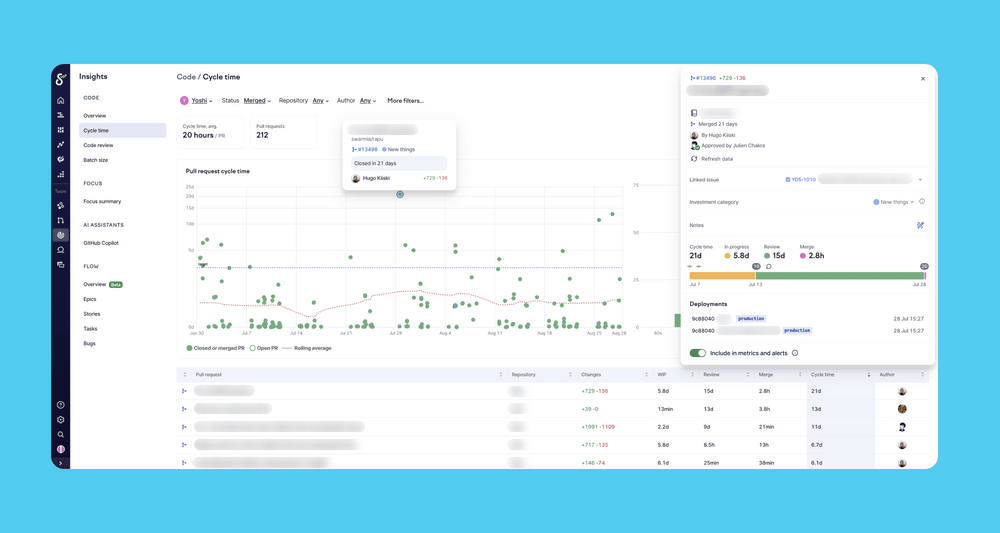

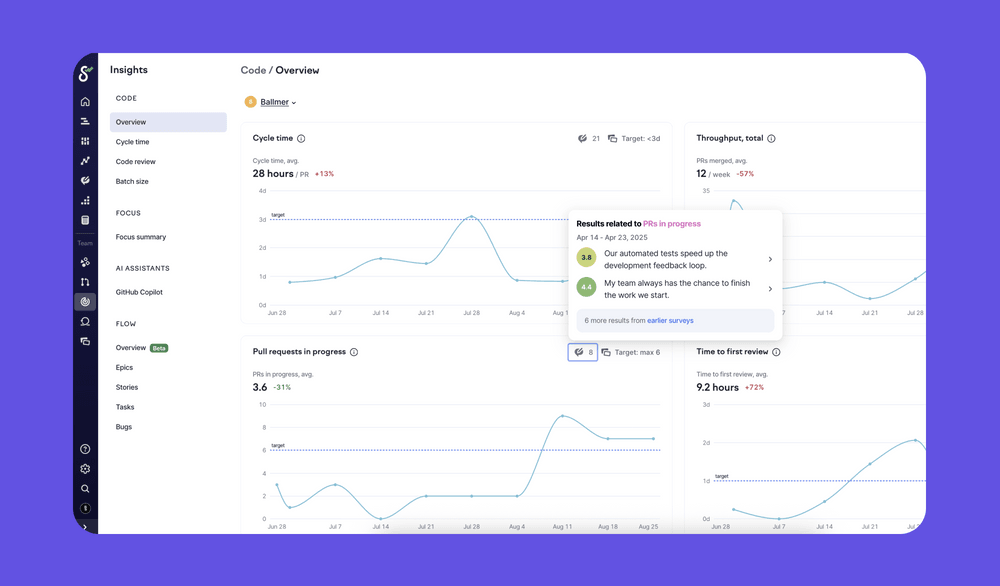

A single number is unlikely to capture the whole truth. You need to be able to tear it apart and see what is actually happening.

Too much focus on individuals

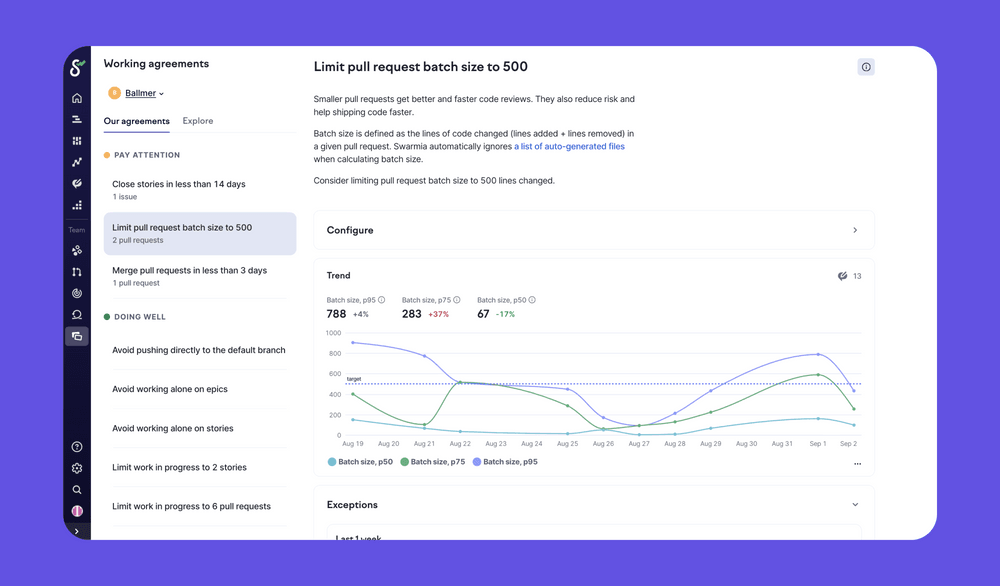

The improvements with the biggest leverage tend to be related to systems rather than individuals.

Software engineering intelligence tools often get positioned as performance management tools, helping managers identify their “top performers” and “underperformers.” This is not how software development works.

When a developer takes down production with a missing semicolon, the problem isn’t the developer — it’s your deployment pipeline that allowed untested code to reach production. When code reviews take forever, the problem isn’t lazy reviewers — it’s probably unclear ownership, missing context, or pull requests that are too large.

A healthy engineering culture treats mistakes as opportunities to improve systems. But when your tool focuses on individual metrics, you end up having the wrong conversations. Instead of asking “how do we prevent this system failure?” you’re asking “who’s to blame?”

The data should help you level up your organization, not rank your people.

Using systemic indicators as performance metrics

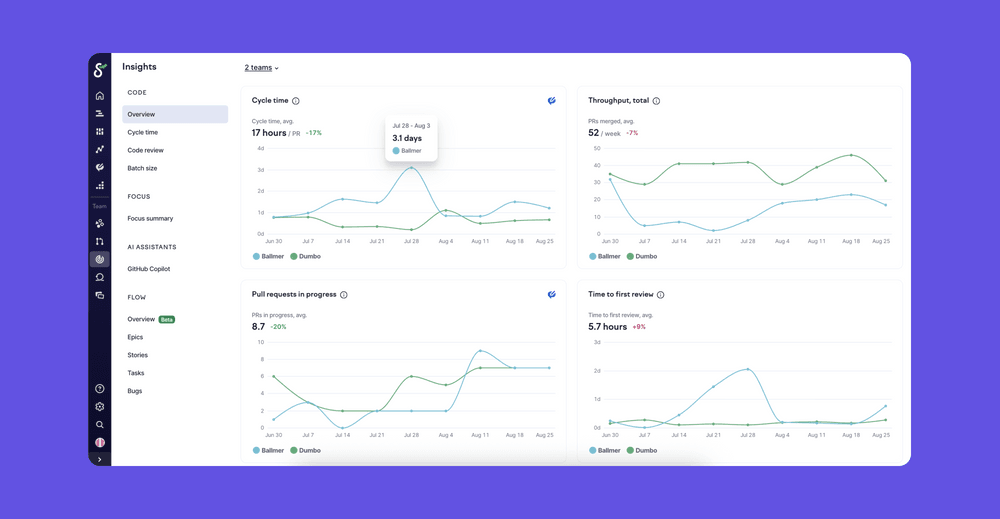

Cycle time — the time it takes to get code to production — is one of the most important metrics for understanding your development process. It reveals bottlenecks in code reviews, testing, and deployment. It’s a team metric.

But some developer productivity tools use cycle time to evaluate individual developers, which completely misses the point. Cycle time is mostly about waiting, not individual performance.

What makes it even worse for measuring performance is the selection bias. You might find that your most senior developers take longer than your junior developers to make a change.

The reason is not surprising: your senior developers are likely working on your most difficult problems. Running a carefully orchestrated migration project is very different from making a copy change on the website.

Assuming that there’s a simple answer

Any time someone claims their “AI measurement framework” can measure productivity with a single number, you should be careful.

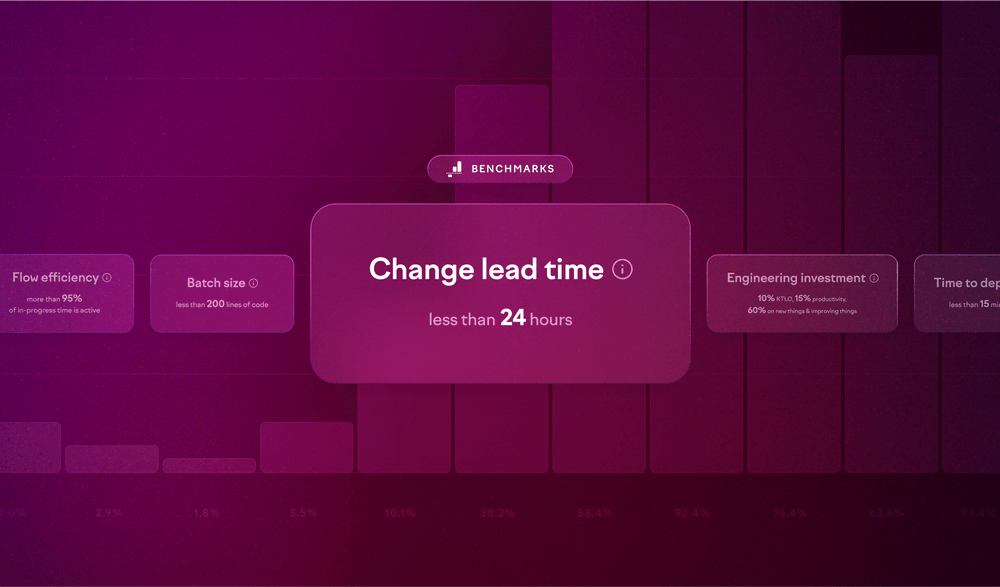

One of the core findings of the SPACE framework paper is that there is no single metric for productivity, but rather you need to look at different dimensions at different levels of the organization.

We’ve all been there with a boss who wants a simple answer, but when it comes to developer productivity, there is none. That’s the reason these tools didn’t become popular already 20 years ago.

Comparing apples and oranges

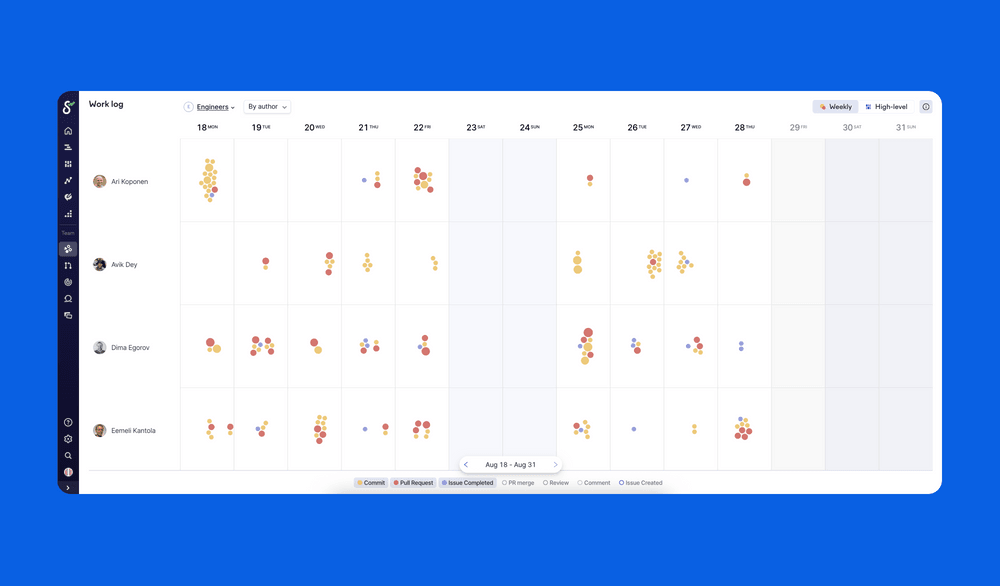

If a table shows a list of your developers with the number of commits next to their name, this design guides the user to expect that these numbers are comparable.

If someone has zero commits, it’s likely true that they were not making any code changes. But what if they were in recruiting meetings all day?

And what if one developer has 7 commits and the other has 5. Is one of them 40% more valuable? Clearly not — commits highly reflect your personal scoping preference.

Breaking developer flow

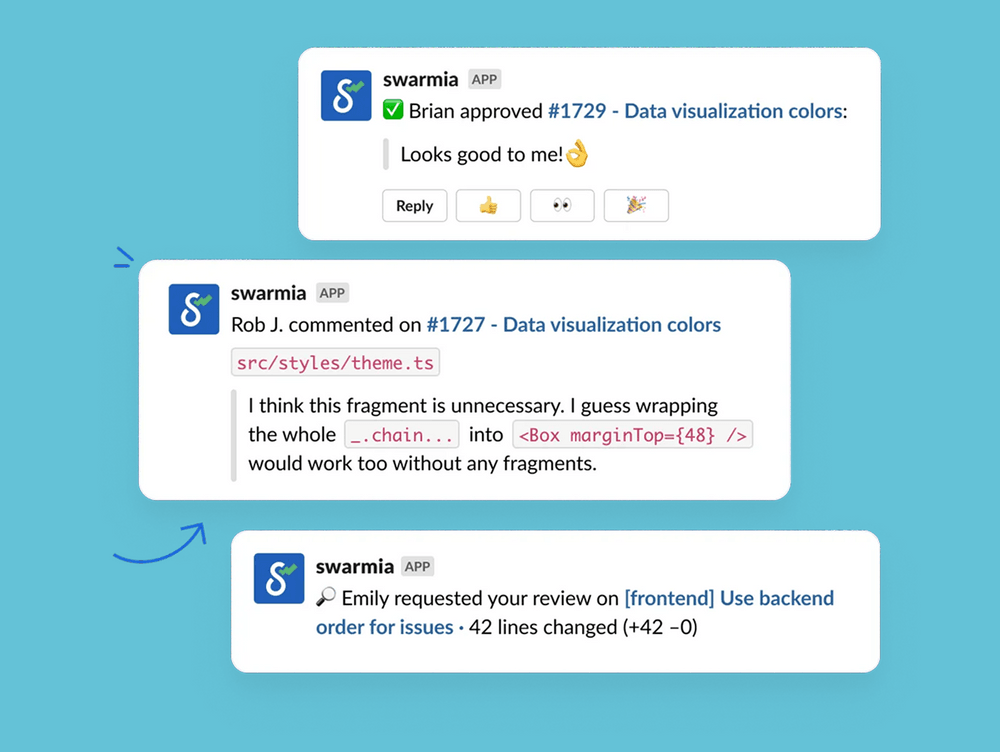

When tools require logging into a separate dashboard and doing something outside of the scope of daily tasks, every visit is a context switch. Developers avoid updating these tools because they’re painful to use, which makes the data even poorer in quality.

It’s an unfortunate cycle that ends with dashboards that nobody trusts.

Measuring activity without asking about experience

Many tools give you metrics about commits, PRs, and cycle times, but never actually ask developers how they’re doing. They measure what developers do, but not how they feel about their work environment or processes.

You might know that deployment frequency is down, but without context, you won’t know if it’s because of a painful CI/CD system or burnout from too much context switching.

System metrics need to be combined with regular developer experience surveys to get the full picture. Otherwise, you’re optimizing metrics while missing the human factors behind them.

So if all of these are the anti-patterns, what should you be looking for instead?

What developers actually want from these tools

When engineering intelligence tools actually work, it’s because they’re built on trust. Developers engage with tools that respect their expertise and help them do better work. Here’s what developers are really looking for:

- Visibility into their own bottlenecks and workflow patterns

- Reliable data to advocate for technical improvements

- Objective evidence to celebrate meaningful wins

- Context and nuance for coaching conversations

- Agency over their own improvement

- Integration with their actual workflows

The cost of getting this wrong

After reading through all these anti-patterns, you might still be wondering: does it really matter? Can’t we just pick a tool and make it work?

The short answer is no.

Developer-friendliness is the difference between a tool that drives improvement and one that drives dysfunction.

If your organization respects developers enough to be transparent with data, trust them to identify and solve problems, and meet them where they work, your productivity will improve — because teams can focus on getting better rather than looking good.

But if your organization tries to measure developers like factory workers, you will get exactly what you’re measuring: developers who optimize for metrics instead of customer value.

The choice is yours. Your developers already know which type of organization you are. The only question is whether you’re honest about it.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest product updates and #goodreads delivered to your inbox once a month.

More content from Swarmia