How engineering effectiveness looks at 10 vs 1000 engineers

At 10 engineers, your biggest risk is building the wrong thing. At 100, it’s teams getting in each other’s way. And at 1,000, it’s the coordination overhead crushing your ability to ship anything at all.

Most engineering leaders hit these inflection points and look to companies that have it figured out. Maybe your CTO returns from a conference convinced that Spotify’s squad model will solve all of your problems, or a board member suggests you implement whatever process worked at their other portfolio company.

The problem is… Spotify has 2700 engineers. That other company might have 400. And you have 20.

Borrowing practices from companies at vastly different scales is how 50-person startups end up with enterprise-grade approval processes, and how 500-person companies ship at the pace of a 10-person team.

None of these stages are inherently bad, they’re just natural evolution points. The challenge is recognizing where you are and solving the problems actually in front of you, not the problems Google solved a decade ago.

First, understand where you are

Before implementing any two-pizza teams or adopting anyone’s squad model, figure out your actual stage:

- Can your CEO name every engineer? You’re at startup scale (roughly 10-30 engineers). Your challenge is maintaining focus amid infinite possibilities.

- Do you need a calendar invite to ship a feature? You’re scaling up (roughly 30-150 engineers). Your challenge is coordination without killing speed.

- Do you have teams whose only job is to coordinate other teams? You’re at enterprise scale (150+ engineers). Your challenge is simplification and empowerment.

At every stage, you’re working with the three pillars of effective engineering organizations: deliver business value, maintain developer productivity, and preserve developer experience. It’s just that how you approach them looks different at each scale.

A quick note on AI coding tools

Successful AI adoption follows a deliberate path: experiment, adopt, measure impact, then optimize for cost. Where you are on this journey isn’t strictly determined by your company size.

What changes with scale is the risk profile and what you need to measure:

- During experimentation: At 10 engineers, individuals can see decent productivity gains even without perfect processes because size provides natural guardrails. At 100+ engineers, you need solid deployment pipelines and testing in place before experimenting safely on production systems.

- During adoption: At 10 engineers, adoption happens organically through conversations. At 100+, you need data on who’s using what you’re paying for, and how.

- When measuring impact: Measure whether AI improves your business performance, not just vanity metrics like lines of code generated or any other aggregated ‘AI impact’ metric. This matters whether you have 50 engineers or 5,000.

- When optimizing for cost: Once you’ve proven impact, you can make informed decisions about which tools to keep, which licenses to cut, and where AI delivers the most value for your investment.

At 10 engineers, speed comes from saying no

When your CEO sits next to your engineers, connecting engineering to business outcomes happens organically. Every engineer can talk to customers, understand which features will close deals, and see their code’s impact immediately. This direct connection is your superpower.

The temptation is to add structure prematurely. You don’t need sophisticated OKRs when finding product-market fit is your only objective. You don’t need quarterly planning when you pivot based on last week’s customer conversations. What you do need is visibility over process — simple tools that show where effort is going so you can answer “what’s everyone working on?” in seconds, not hours.

Your developer productivity challenge isn’t velocity — most 10-person teams ship fast when they know what to build. Your challenge is maintaining focus. At this scale, saying no is more important than shipping fast. The team that ships five mediocre features loses to the team that nails one critical capability.

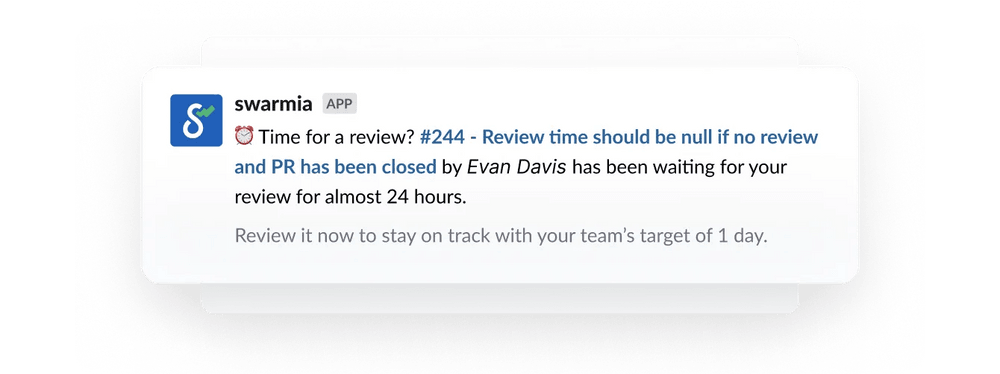

Establishing lightweight measurement now (like tracking basic PR cycle time and getting Slack notifications for reviews) makes the transition smoother as you scale past 30 engineers. Not to hit targets, but to notice when things start to slow down.

Developer experience at this stage is about building healthy practices that will scale. Establish psychological safety now — when someone breaks production, the response should be “what can we change?” not blame.

The informality you have now is an advantage: every engineer understands the whole system and has complete autonomy and freedom to experiment. Larger companies spend so much of their time trying to recapture this.

At 100 engineers, the wheels fall off

Somewhere along the way to 100 engineers, informal networks hit their natural limits.

The CTO can no longer join every retro, and when one team’s feature affects three others’ systems, lunch conversations about the solution don’t cut it anymore.

Managing cross-team dependencies becomes one of the hardest coordination challenges at this scale. You need architectural patterns that reduce coupling, clear ownership boundaries, and regular communication between teams to surface blockers early. The challenge at this stage is adding just enough structure to maintain alignment without crushing speed.

The first time leadership can’t reliably answer: “Where is engineering effort actually going?” is about the time you need to invest in systematic visibility.

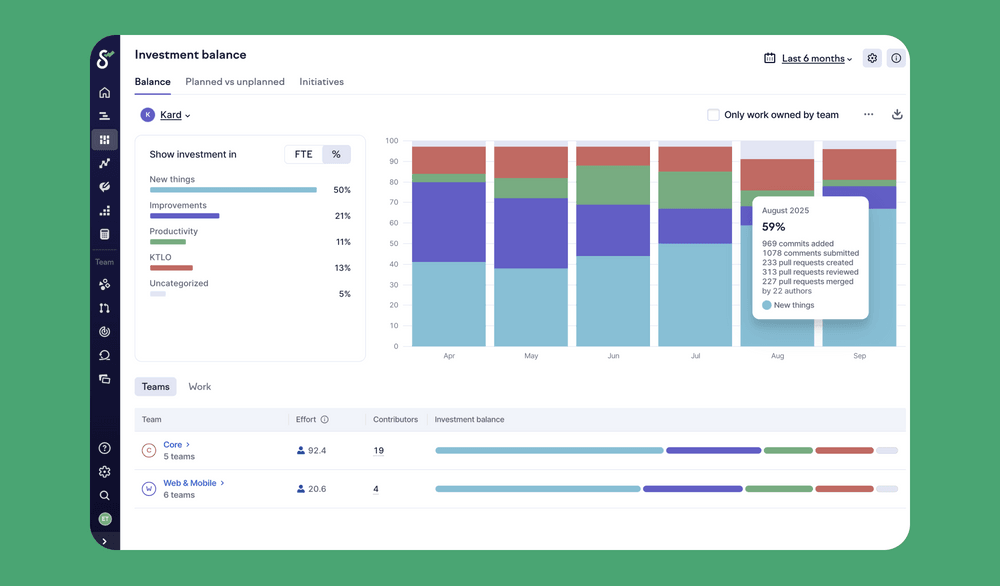

Investment balance shows where effort goes — new features, improvements, keeping the lights on, or productivity work. When you can show that Team A spends 80% of their time keeping the lights on, it’s easier to make the case for refactoring or additional headcount.

If you’re already deploying continuously and have fast feedback loops in place, DORA metrics mostly confirm you're doing things right. But many companies at this scale are dealing with inconsistent deployment practices, slow CI/CD, and teams working in different ways — which is when DORA metrics help surface problems and track improvements.

Some variation between teams is normal — your infrastructure team might deploy weekly while your frontend team deploys hourly. Both can be optimal. The goal isn’t uniformity, but understanding whether each team’s metrics reflect their reality or reveal problems.

Finding the right balance of standardization is the challenge — things like shared tooling, code review practices, and deployment processes. Too much, and you’ve created a 100-person company that ships at the pace of a 1,000-person enterprise. Too little, and teams can’t help each other.

And as you start measuring systematically, you’ll also want to understand whether your investments in AI coding tools are delivering business outcomes. Measuring the productivity impact of AI might still be a bit murky, but you should at least be keeping track of adoption and usage across your organization.

As you grow, variance in developer experience becomes significant — one team has excellent tooling while another struggles with basic workflows. The solution is making common work excellent, whether that’s through shared tooling across teams or a dedicated platform team. Most companies do indeed form their first platform team somewhere around 50 engineers, but the key is ensuring whatever your company does a lot of, it gets really good at doing.

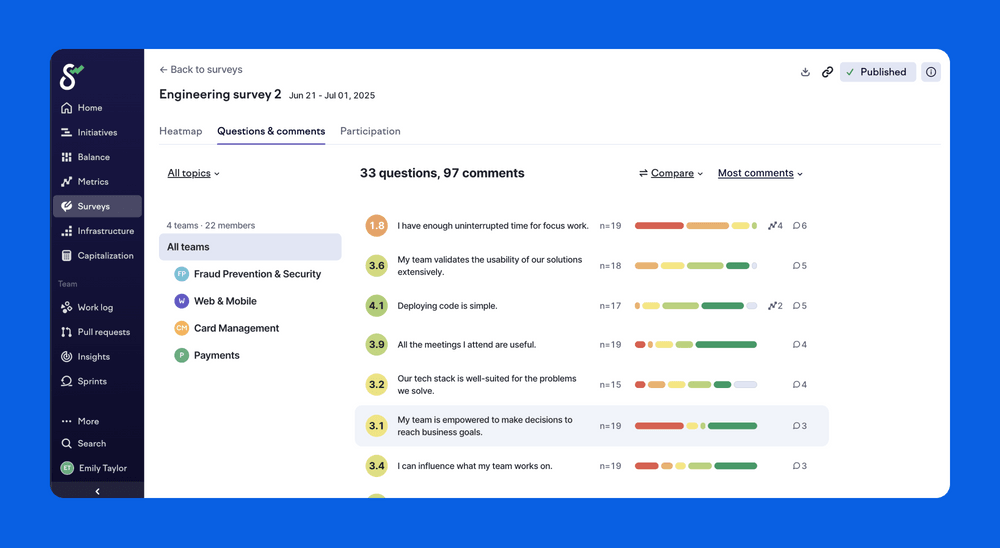

Developer experience surveys become essential at this stage too, with regular check-ins that help you (leadership) and the platform team identify and prioritize improvements. They also give you a more representative sample, rather than only hearing a handful of the loudest voices. The key is closing the loop — showing engineers how their feedback led to concrete changes maintains trust in the system.

At 1,000 engineers, small gains compound

When you have 1,000 engineers, no single person can hold the entire system in their head.

Multiple layers of management, complex stakeholder networks, and competing priorities are realities that just need to be managed.

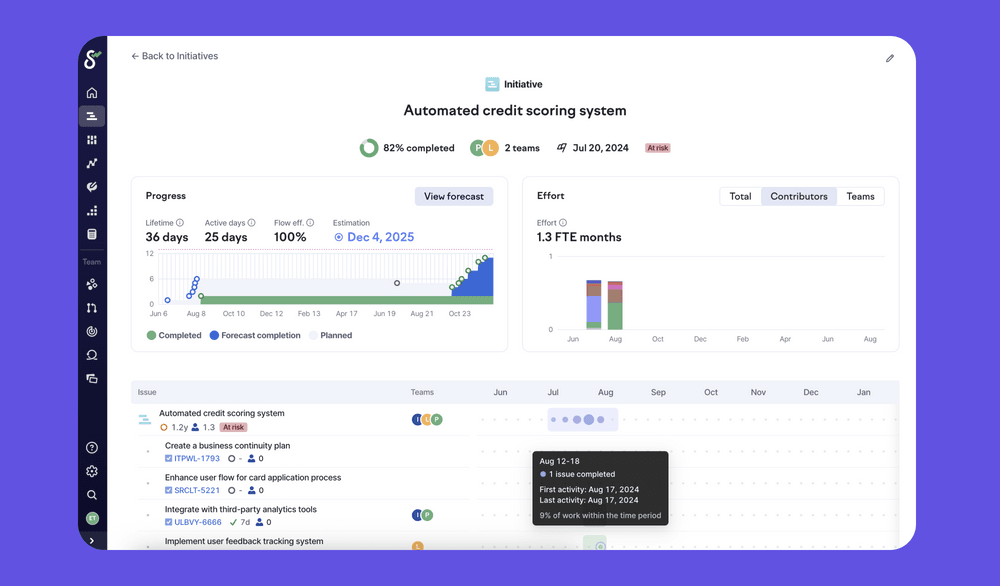

Effective enterprise organizations create autonomous teams within clear boundaries and push decisions down to people closest to the work. But autonomy only works with visibility. When the board asks about progress on the initiative that will save a key customer, you need to show exactly which teams are involved, what percentage is complete, and whether you’ll hit targets.

And when finance needs software capitalization reporting for your quarter-end filing, you need to show what counts as capitalizable development without asking every engineering manager to fill out spreadsheets.

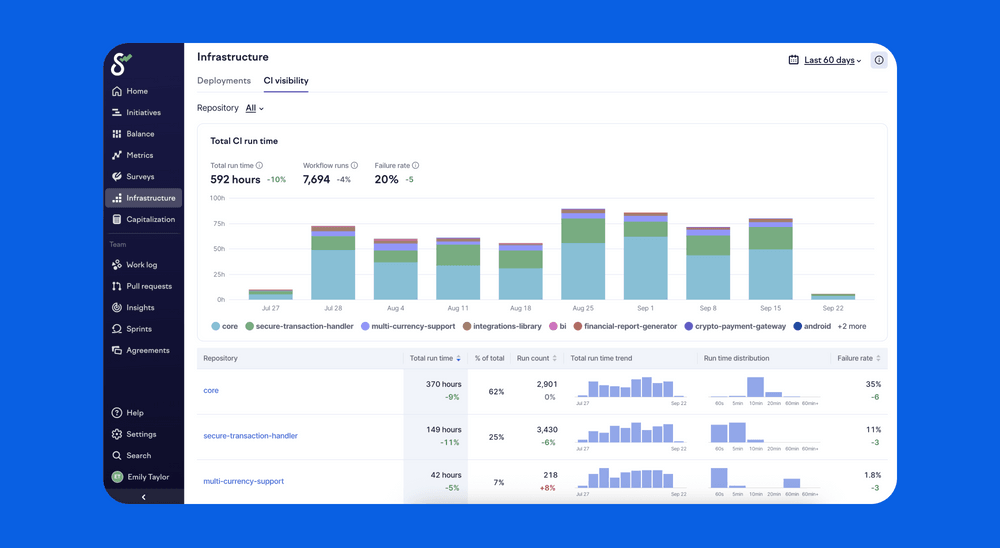

Developer productivity at this scale is about marginal gains across systems, not individuals. A 10% improvement in build time sounds modest, but across 1,000 engineers it’s massive. Understanding where builds fail through CI insights can save hundreds of engineer-hours monthly.

When a flaky test causes 20% of builds to fail, every engineer hits it multiple times per week. They context switch, investigate, realize it’s not their fault, retry, and lose momentum. Fix that one test, and you’ve given 1,000 engineers their flow back.

And finally, about developer experience in enterprise engineering organizations: you should be treating developer experience as an internal product.

Platform teams that treat engineers as customers with competing needs build tools people actually use. They maintain backlogs, run usage analytics, and have direct feedback channels. When teams ignore your internal tools, it’s not an adoption problem, but a product-market fit problem.

Running regular developer experience surveys, combined with internal tooling analytics, can help platform teams build what engineers actually need rather than what they assume engineers want.

Start where you are, build for where you’re going

You don’t need perfect metrics or flawless processes. You need to understand where you are, where you’re going, and what challenges await you at the next stage.

Start with one problem holding your team back today. Fix it. Measure whether it actually helped — maybe with metrics, maybe just by asking your engineers: “Is this better than before?”

As you grow, the problems will change, but the approach remains the same: maintain visibility, preserve team autonomy even as you add coordination, and keep engineers connected to the impact of their work.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest product updates and #goodreads delivered to your inbox once a month.

More content from Swarmia