- Product

- Changelog

- Pricing

- Customers

- LearnBlogInsights for software leaders, managers, and engineersHelp center↗Find the answers you need to make the most out of SwarmiaPodcastCatch interviews with software leaders on Engineering UnblockedBenchmarksFind the biggest opportunities for improvementBook: BuildRead for free, or buy a physical copy or the Kindle version

- About us

- Careers

Engineering metrics leaders should track in 2026 (and what to do with them)

Most advice about engineering metrics treats them like a shopping list: pick DORA, add some SPACE dimensions, throw in some cycle time, done.

But this approach ignores an important question: who needs this metric, and what will they do with it?

As an engineering leader, you need metrics that help you understand organizational health, identify systemic issues, communicate with stakeholders, and make confident decisions about where to invest. But you also need metrics that help your teams improve — not just optimize for a number.

Below, we’ll cover 12 essential engineering metrics for leaders, organized by what they actually help you understand: delivery performance, development flow, resource allocation, and team health — as well as what to do when these metrics start trending in an unwanted direction.

Engineering metrics for teams versus about teams

Before getting into specific metrics, you need to understand an important distinction that most conversations about metrics gloss over: not all metrics share the same purpose.

Engineering leader and organizational developer Lena Reinhard has a useful framework for thinking about this:

- Engineering metrics for teams are the ones teams actively use to improve. These show up in retrospectives, inform working agreements, and help teams spot their own bottlenecks. A team looking at their review time metrics and deciding to set up Slack notifications for waiting PRs — that’s a metric working for the team.

- Engineering metrics about teams give engineering leaders organizational visibility. These often work best in aggregate, showing patterns across multiple teams or tracking progress on company-level goals. When you compare deployment frequency across domains to identify where teams might need platform support, those are metrics about teams.

The difference is important, because forcing teams to optimize metrics they don’t find useful breeds cynicism and gaming. Meanwhile, keeping organizational health metrics hidden from teams breaks trust. The goal should be transparency about both types of metrics, with clarity about their purpose.

Of course, some metrics do serve both purposes. Cycle time is one example, because it can both a) help teams identify where work gets stuck, and b) help leaders uncover issues across teams. You just need to be clear about how you’re using the data.

You can hear more from Lena about this concept and her approach to metrics in her conversation on the Engineering Unblocked podcast.

Software delivery performance metrics

We can’t write an article about engineering metrics without starting with DORA. DORA metrics are usually used to talk about teams, but because they’re essentially a shared language across engineering for understanding delivery health, they’re used both by engineering leaders and teams, albeit in different ways.

DORA metrics provide the clearest picture of your organization’s delivery capability and stability. And while many people still refer to the “four DORA metrics,” the framework actually evolved to include five metrics as of 2024.

The metrics are now grouped into two categories: throughput (how fast you can deliver) and instability (the quality and reliability of that delivery).

For high-performing teams, these metrics often stay healthy without active optimization. They’re an outcome of good practices, rather than a target to chase — think of them like a thermometer. Where DORA metrics become valuable is in spotting systemic issues across your organization, and keeping an eye on whether your engineering effectiveness efforts are actually working.

1. Deployment frequency

Deployment frequency is how often your organization ships to production. Elite teams (we’re talking about web-based software teams here, not mobile teams) deploy on demand, potentially several times a day. Infrequent deployers batch up large releases, and large releases generally cause large problems.

What it tells you: This metric works as a proxy for batch size and overall delivery capability. Deployment frequency dropping across multiple teams signals problems with your delivery infrastructure or growing process bottlenecks.

What to do about it: Examine your release process for manual steps, approval gates, or anxiety about deployments breaking things. Feature flags can help by separating deploying code from releasing it to users.

2. Change lead time

Change lead time is the time between when a task is started and when the resulting code is in production. Elite teams manage this in under a day. For some teams, it can stretch to a month or more.

What it tells you: When change lead time balloons, the work is spending most of its lifetime waiting — for code review, for QA, for a deployment window. The actual hands-on-keyboard time might be hours, but the total elapsed time weeks.

What to do about it: If the goal is to reduce the amount of waiting time, a good place to start is introducing WIP limits, breaking work into smaller chunks, and investing in CI/CD and automated testing.

3. Failed deployment recovery time

Failed deployment recovery time is how fast you get back to a working state when something goes wrong. Previously known as mean time to recover (MTTR), this metric was refined in 2023 to focus specifically on failures caused by software changes rather than external factors like infrastructure outages.

What it tells you: This metric reveals the maturity of your incident response processes. Recovery time increasing across teams signals that your monitoring, runbooks, or rollback capabilities need work.

What to do about it: Make sure you have monitoring that catches incidents quickly, documented runbooks for common failures, and the ability to roll back or disable features instantly. How you respond to incidents directly affects this metric — if the company response is finding someone to blame, people will hide problems rather than surfacing them quickly.

4. Change fail rate

Change fail rate (previously change failure rate) is the first of the two instability metrics, and is defined as the percentage of deployments that require immediate intervention following deployment. So think outages, rollbacks, and urgent hotfixes.

What it tells you: A certain amount of failure is healthy because it means you’re shipping and learning, and zero failures usually means you’re not taking enough risk. But if more than a quarter of your deployments cause issues, something’s wrong with your quality gates.

What to do about it: High failure rates almost always respond to better automated testing and smaller batch sizes. If the rate is climbing across teams, you might have quality problems or teams taking shortcuts under pressure.

5. Deployment rework rate

Deployment rework rate is the percentage of deployments that are unplanned, but happen as a result of an incident in production. This metric was added to the DORA metrics in 2024, and it helps teams understand how much of their deployment activity is reactive, rather than planned feature work.

What it tells you: High rework rates tell you that teams are spending significant time fixing production issues instead of delivering new value, which is not optimal.

What to do about it: Like change fail rate, this metric improves with better testing practices and smaller batch sizes. But it also points to whether you’re accumulating technical debt or working on systems that need architectural improvements.

A note on reporting up before we move on: DORA metrics provide useful data for executive conversations about engineering performance, but the numbers alone don’t tell the full story. Focus on trends over time and what they reveal about your organizational capability.

If metrics are trending negatively, come prepared with your hypothesis about root causes and your plan to address them. And if they’re improving, connect those improvements to specific investments you made (better CI/CD, platform improvements, smaller batches, improved testing) and the business impact those changes enabled.

Understanding where work gets stuck

These engineering metrics are mostly for teams — they help teams identify their own productivity bottlenecks and drive daily improvements. As a leader, you’ll use them in aggregate to monitor patterns across teams.

6. Cycle time breakdown

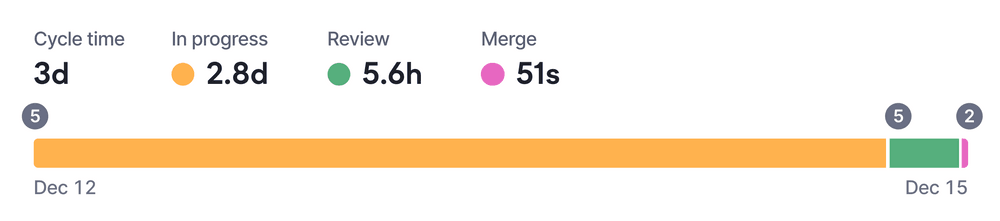

Cycle time is the total time a pull request spends in all stages of the development pipeline. It’s similar to change lead time above, but doesn’t include time to deploy. How different organizations define the stages can vary, but regardless, breaking it into stages can help reveal exactly where work gets stuck:

- Time in progress — from the first commit or from when the pull request is opened, whichever happens first, to the first review request.

- Time in review — from the first review request (or from when the pull request was opened, if none) to the final approval.

- Time to merge — from the final approval to once the pull request is merged.

What it tells you: This breakdown reveals patterns you can’t see at the team level. If one team’s review stage consistently takes three times longer than others, that’s worth investigating. Maybe they’re understaffed, maybe they have a knowledge silo, or maybe their codebase is genuinely more complex.

What to do about it: Use cycle time to identify patterns, rather than trying to drive improvement on any single team. When you see significant variance, your first conversation should be with the team’s lead or a senior developer to understand context before jumping to solutions.

7. Batch size

Batch size is the number of code lines changed (added + deleted) in a pull request. Smaller changes get reviewed faster and more thoroughly, and most teams see real improvements when they keep changes under 400 lines.

What it tells you: Large PRs slow down everything. They take longer to review because they require more context, and people avoid picking them up. This creates a vicious cycle where large PRs sit longer, which encourages developers to batch up even more work before opening the next one.

What to do about it: Help teams establish working agreements around PR size. Track the metric over time to see if the agreements are working. If PRs are routinely large, dig into why — sometimes it’s the nature of the work, but often it’s unclear requirements or lack of feature flags to hide work in progress.

8. Time to first review

Time to first review (the gap between opening a PR and getting a first look) is where most delays happen. Engineers finish their work, open a PR, and then nothing happens for days.

What it tells you: Long pickup times signal that code review isn’t prioritized or that notifications (if they exist) aren’t reaching the right people. This metric often reveals a cultural issue more than a technical one.

What to do about it: Slack notifications that surface waiting PRs can cut this time dramatically. Help teams establish working agreements around review turnaround time — many teams aim for reviews to start within 4 hours.

9. Build time and CI feedback speed

If your CI pipeline takes 30 minutes and developers run it five times a day, that’s 2.5 hours of waiting per person. Across a team of eight, that adds up to around 100 engineering hours a week. At enterprise scale, that number gets very big, very fast.

And sure, you can go and work on a bunch of other stuff while you’re waiting, but that comes with its own set of problems.

What it tells you: Build times directly impact how fast developers can iterate. Slow CI pipelines create a bottleneck in the development flow — developers either wait for builds to complete or context-switch to other work, both of which slow down delivery and increase cognitive load. Long or unreliable feedback loops make it harder to keep work moving smoothly.

What to do about it: Shaving even a few minutes off a frequently run build can save hundreds of engineering hours over a year. Look for opportunities to speed up CI by parallelizing jobs, caching dependencies, or splitting slow test suites. Treat fast, reliable feedback as core delivery infrastructure, not an optimization to tackle “later.”

Understanding where engineering effort goes

These are less hard-and-fast engineering metrics, but they certainly help you make informed decisions about resource allocation and have data-informed conversations about engineering capacity.

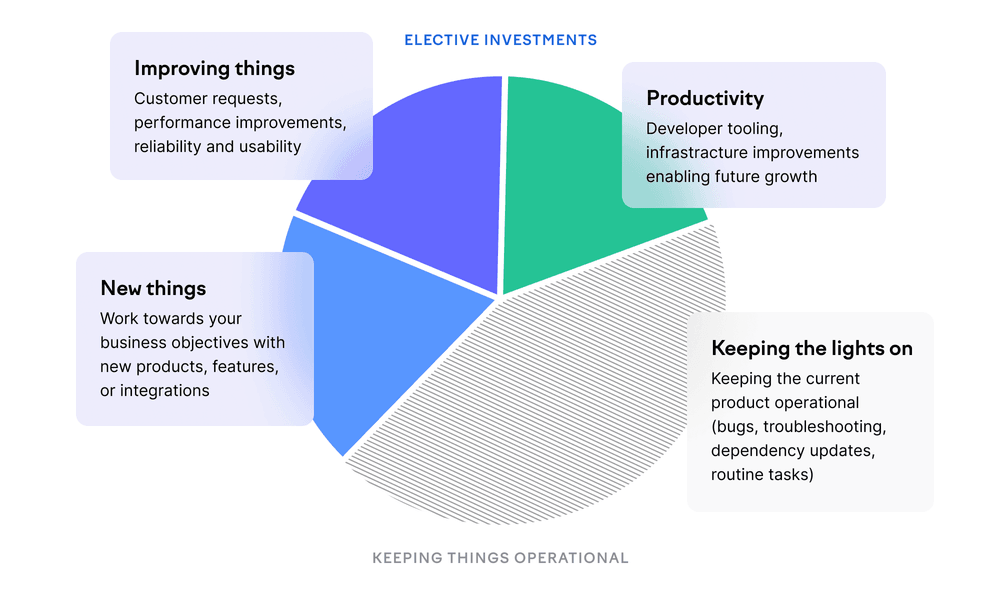

10. Investment balance

Investment balance is the percentage of time spent on new things, improvements, productivity, and keeping the lights on. Before having a reliable measurement of your org’s investment balance, the difference between where most leaders think engineering effort goes versus where it actually goes can be quite an eye-opener.

What it tells you: Without visibility here, you’ll assume most engineering time goes toward building new things, or making improvements. The reality is often different — many teams spend 40-50% of their time on maintenance and unplanned work. Some systems need more upkeep than others, so this isn’t inherently bad. But if your roadmap assumes 80% feature capacity and reality is 50%, you’ll keep missing commitments.

What to do about it: Investment balance is most valuable as a conversation starter. When you can show that a team spends 80% of their time keeping the lights on, it’s easier to make the case for refactoring or additional headcount. At the organizational level, track investment balance to understand whether your allocation matches strategic priorities.

This is powerful data for executive and board conversations about engineering capacity. When stakeholders push for more features, you can show exactly where engineering time is going and make informed tradeoffs about what to deprioritize.

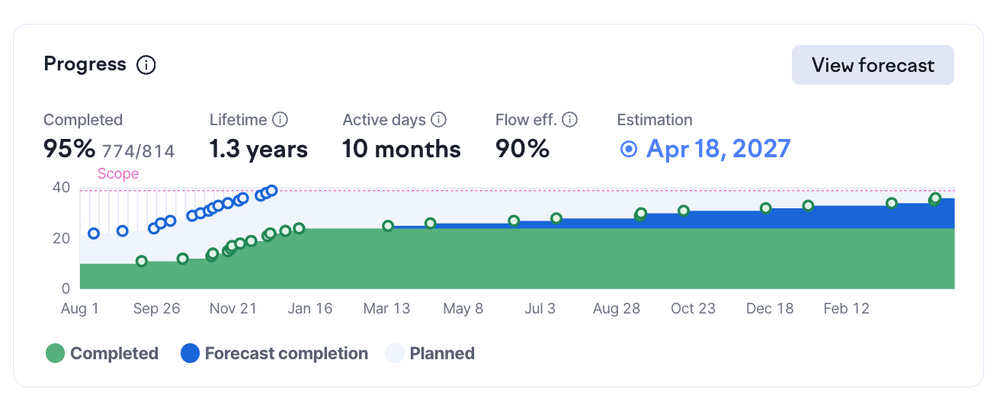

11. Planning accuracy

Planning accuracy tracks what teams planned to ship versus what actually shipped. You can track this a bunch of different ways, depending on whether you use deadlines and how you estimate work (as long as it’s not using story points, you’re good).

What it tells you: This matters more at scale, when predictability becomes important for coordinating across teams and communicating with stakeholders. Consistently low accuracy suggests problems with estimation, scope creep, or interruptions. Consistently high accuracy is a good problem to have, but it could mean teams are being too conservative.

What to do about it: Treat planning accuracy as a diagnostic rather than a target (no “we must hit XX% accuracy in H2”) and use it to identify teams that might need help with estimation or that are dealing with excessive interruptions.

Developer experience metrics

Numbers tell you what’s happening, but not why — or whether your engineering organization is a place people want to stay. Research shows that developer experience directly impacts both engineering productivity and your ability to deliver on planned business outcomes. Poor developer experience not only costs you talented people, but slows down everything your teams are trying to accomplish.

12. Developer survey data

Survey data captures what metrics miss: whether engineers feel productive, whether tools help or frustrate them, whether they have enough uninterrupted time for deep work, and whether they understand how their work connects to business goals.

What it tells you: Developer experience directly affects retention, and replacing engineers is expensive. Survey data often uncovers issues that system metrics miss — like a cumbersome deployment process, lack of psychological safety, or meeting overload.

What to do about it: The key is asking questions you can act on. “Rate your job satisfaction from 1-5” produces a number without context, while “Our automated tests catch issues reliably.” gives you something to fix. Run developer experience surveys regularly (quarterly tends to work well for org-wide surveys) and close the loop to show how peoples’ feedback led to changes.

Codebase health signals

As an engineering leader, you might be thinking more and more about code quality — especially as teams adopt AI coding tools and ship more changes faster, sometimes with less scrutiny. The challenge is that most traditional code quality metrics are easy to misunderstand and misuse, and hard to act on without context.

Codebase health is critical for long-term delivery and risk management, but these signals work best as indicators of risk, not performance targets.

- Code coverage (track trends, not targets): Test coverage is most useful when you look at how it changes over time, especially in fast-moving or high-risk parts of the codebase. Declining coverage alongside increasing change suggests that risk is accumulating faster than it’s being paid down. Stable coverage in stable systems is often fine.

- Code churn (where change is concentrated): Churn shows where code is being rewritten frequently. High churn can reflect learning, refactoring, or unclear requirements; low churn in critical systems can signal fear of touching brittle code. Use churn to decide where to ask questions, not to tell teams to “rewrite less.”

- Codebase risk (rather than a single “quality” score): Instead of scrutinizing code quality metrics directly, look at where technical risk shows up in outcomes: repeated incidents, rising rework, slower recovery times, and longer review cycles. These patterns often reveal systems that are becoming fragile or expensive to change.

Used this way, codebase health metrics help engineering leaders decide where to invest — in refactoring, platform work, or ownership changes — without turning quality into a scoreboard.

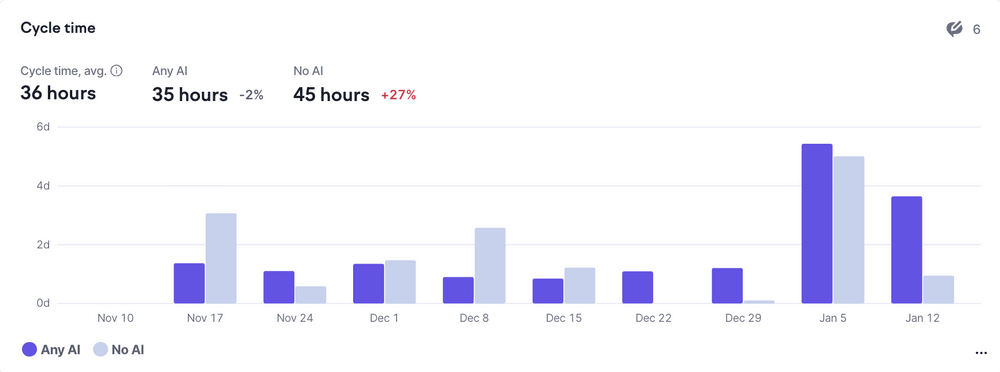

Measuring the impact of AI coding tools

If your teams are using AI coding assistants, you’re probably fielding questions about ROI. Resist the urge to find a single “AI productivity KPI” that proves the investment is paying off.

What works better is examining your existing metrics with an AI lens. Segment cycle time, batch size, and time in review by whether AI tools were involved. Are AI-assisted PRs moving faster? Are they taking longer to review? Those questions should be your conversation-starters.

When you find differences — and you will — avoid jumping to conclusions. If AI-assisted PRs have shorter cycle times, that might mean:

- AI genuinely helps developers work faster

- Your most experienced engineers (who naturally work faster) are the keenest adopters

- Teams with strong fundamentals are both faster and more likely to experiment with new tools

Each explanation suggests different actions, which is why careful analysis beats quick ROI claims.

The clearest finding from research so far: AI amplifies existing patterns. Teams with solid practices — good test coverage, clean codebases, fast feedback loops — see benefits. Teams with shaky foundations find that AI helps them produce more code with the same underlying problems.

When metrics go wrong

The most common failure mode is using engineering metrics to evaluate individuals. Commits per day, PRs merged, lines of code written — these numbers are easy to collect but they almost always measure the wrong thing.

Software development is collaborative. The engineer who spends a day helping three teammates get unstuck has contributed enormously, but their commit count is zero (and so what?) The engineer who writes a thousand lines of code that creates technical debt for years shows up great on some activity metrics.

And then there’s Goodhart’s Law, that gets touted a lot in metrics discussions: when a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure.

The solution is transparency and shared ownership:

- Make metrics visible to everyone, not just management

- Be clear about which metrics are for teams to use and which are about teams for organizational visibility

- Involve teams in selecting the metrics that matter to them

- Use aggregate data and trends for leadership decisions rather than diving into individual performance

- When setbacks happen, ask “what can we learn?” rather than “whose fault is this?”

If you have to explain why you’re tracking something, or if teams feel surveilled rather than supported, you’ve chosen the wrong metrics or communicated poorly about their purpose.

Start with one problem

If you’re not tracking any engineering metrics today, resist the urge to instrument everything at once. Pick one problem you can actually feel — slow code reviews, unpredictable delivery times, too much time firefighting — and measure that. See if you can improve it. Check whether the improvement stuck.

Once you’ve got that working, decide whether it deserves active management as a KPI or whether it’s just a useful diagnostic to check periodically. Then pick the next problem.

The specific metrics matter less than building the habit: looking at data, asking what it means, deciding what to do, following through, and being clear about who the metric serves and what they’ll do with it.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest product updates and #goodreads delivered to your inbox once a month.

More content from Swarmia